OIG Exclusions are powerful enforcement sanctions that bar an individual or entity from any participation in Federal and State health care benefit programs. Programs will not pay for items or services provided by an excluded party, and providers that employ or contract with them risk the imposition of civil money penalties and significant overpayment liability. The focus of this article is to help providers understand their obligations with respect to exclusions, the risks they face if they fail to meet them, and how best to avoid those risks.

I. What is an OIG Exclusion?

OIG Exclusions are administrative sanctions that bar entities who present a risk to beneficiaries and health care programs from all participation in those programs. [1] The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which is responsible for all Federal health care programs, delegated the authority to enforce federal exclusion regulations to its Office of Inspector General(HHS/OIG) [2] and to maintain and update the “List of Excluded Entities and Individuals” (the “LEIE”).

The use of exclusions as an enforcement tool to bar program participation by identified “bad actors” is not new. Congress initially authorized the exclusion of physicians under certain circumstances in Medicare and Medicaid Medicare-Medicaid Anti-Fraud and Abuse Amendments of 1977.[3] The current framework of mandatory and permissive exclusions was then established by the Medicare and Medicaid Patient and Program Protection Act of 1987.

II. Why are OIG Exclusions Imposed?

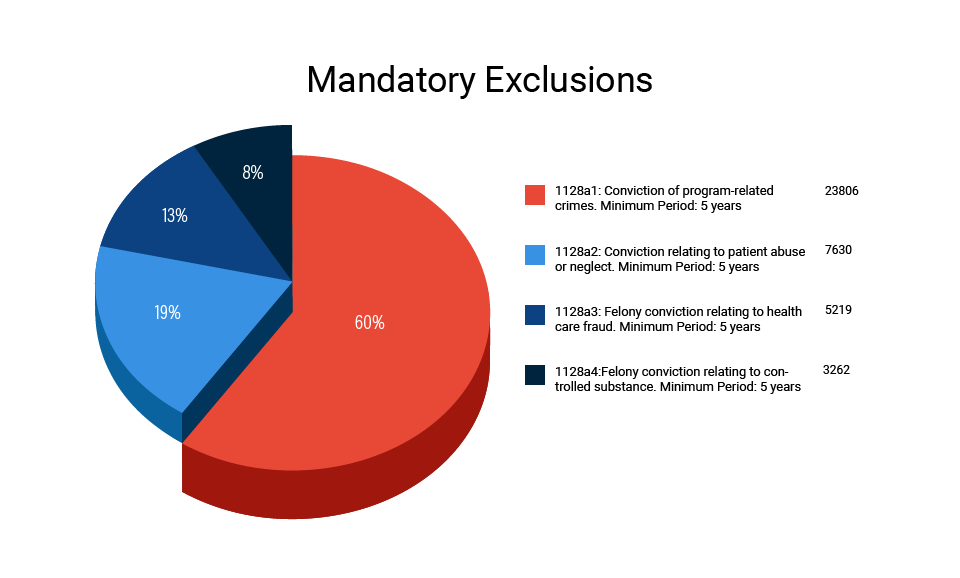

There are two types of OIG Exclusions: Mandatory and Permissive. Mandatory Exclusions last a minimum of five years and are based on criminal convictions under the following circumstances: 1) Convictions related to the delivery of service to a federal or state health care programs, 2) Convictions relating to neglect or abuse; 3) Felony convictions relating to a health care fraud program other than Medicare or Medicaid, and 4) Felony convictions relating to the unlawful manufacture, distribution, prescription, or dispensing of a controlled substance.[4]

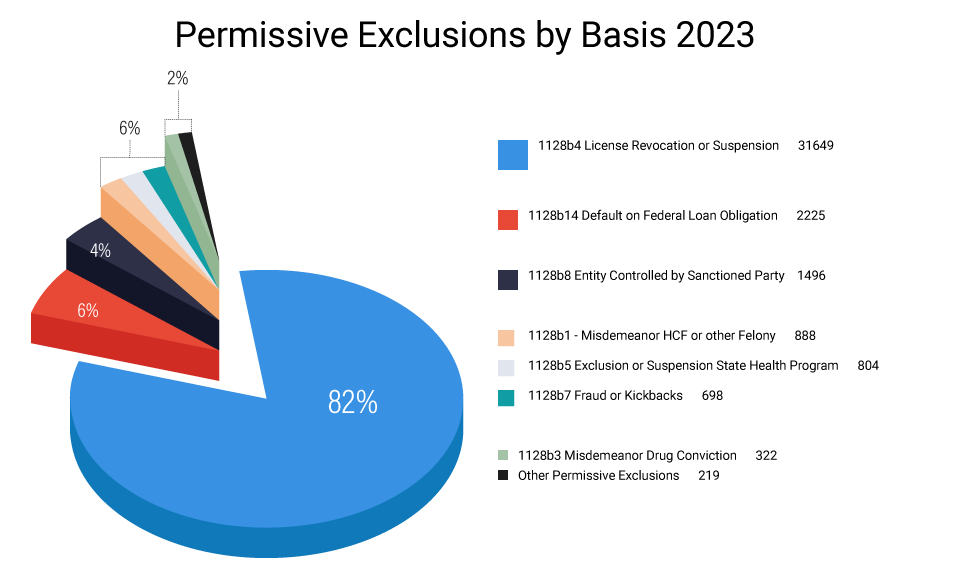

Permissive Exclusions, on the other hand, are generally imposed for at least three years (there are some exceptions) and there is a much wider range of conduct for which they may be implemented. By way of example, these include (but are not limited to) the following:[5]

- Suspension, revocation, or surrender of a license to provide health care for reasons bearing on professional competence, performance, or financial integrity,

- Misdemeanor convictions related to defrauding a health care fraud program,

- Misdemeanor convictions relating to the unlawful manufacture, distribution, prescription, or dispensing of controlled substances,

- Provision of unnecessary or substandard services;

- Submission of false or fraudulent claims to a Federal health care program,

- Engaging in unlawful kickback arrangements,

- Defaulting on a health education loan or scholarship obligations, and

- Controlling a sanctioned entity as an owner, officer, or managing employee

Mandatory Exclusions make up slightly more than half of all exclusions. The following chart shows that a majority of the exclusions are related to convictions for fraud against health care fraud programs, but that there are a substantial number of exclusions under all of the categories.

While there are many more legal bases for the imposition of permissive exclusions than mandatory (18 in all), the chart below demonstrates that the distribution is much different and that the vast majority of these exclusions are based on actions relating to the loss, suspension or surrender of a professional license.

III. The Broad Impact of Exclusions

An OIG Exclusion is broadly designed and interpreted to block any involvement from or by an excluded party. This extends to federal health care programs, which cover any plan or program, such as Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE, or any other program offering health benefits either directly or indirectly. These programs will not pay for any goods or services provided directly or indirectly by an excluded individual or entity, or those that are medically directed or prescribed by an excluded person.[6]

This “payment prohibition” represents an absolute ban on payment, applicable to “all modes of Federal program compensation,” irrespective of its origin, be it an itemized claim, cost report, capitated payment, or other forms of consolidated payment. Its scope is far-reaching, going beyond immediate patient care to include services rendered by excluded individuals affiliated with a hospital, nursing home, home health agency, or managed care entity, whether these services are separately billed or incorporated in a bundled payment.[7]

To explain the scope of the ban, the OIG identified the following examples of activities that could lead to civil monetary penalties and overpayments:

- Management, administrative and any leadership positions;

- The handling claims processing and information technology tasks;

- Offering transportation services with an excluded ambulance driver or dispatcher;

- Selling, delivering, or refilling orders for medical equipment or devices;

- Preparing surgical trays, reviewing treatment plans, and providing other supportive services, billed individually or as part of a bundled payment.

The payment prohibition is further extended to providers who deliver goods or services based on orders or prescriptions from others. Hence, providers such as laboratories, imaging centers, and pharmacies should verify, at the service point, that the ordering or prescribing physician is not excluded to avoid liability. Any failure in doing so may breach the payment prohibition and could lead to both overpayments and CMPs. According to the OIG, even unpaid volunteers can potentially instigate overpayment and CMP liability unless the goods or services they deliver are “completely unrelated to Federal Health Care Programs.”[8]

IV. What is the Process for Getting Excluded? And for Getting off the Exclusion List?

Exclusions are administrative sanctions that can only be sought by the OIG. While the processes of imposing, appealing, and/or removing their designation are impacted by the type of exclusion and governed by regulation,[9] the ability to challenge outcomes once the process has begun is generally extremely limited. For example, if the OIG seeks to impose an exclusion based on a conviction or licensing action (as is the case in all mandatory exclusions and most permissive ones), the defendant is not able to question the underlying conviction action upon which the OIG seeks the exclusion and the ability to contest or appeal the exclusion is limited to its length.

Reinstatement, or getting “off” the exclusion list, does not automatically take place when the term of exclusion has been completed. An excluded party must apply for reinstatement and must demonstrate to the satisfaction of the OIG that they no longer pose a threat to either beneficiaries or to the program. Since that process often includes resolving licensing or restitution-related issues, it can be very challenging for some.

Regardless of the basis, both types of exclusion have the effect of barring an individual or entity from participating in all Federal health care programs from the time they are excluded until such time, if ever, that their privilege is reinstated.

V. The Risk to Providers that Employ or Do Business with Excluded Parties

Since Federal health care programs will not pay for any item or service, any claim submitted, or any actions taken by a person that violates the “payment prohibition,” is subject to overpayment liability and the imposition of Civil Money Penalties (CMPs) liability for exclusion violations.[10] Overpayment liability is particularly problematic where the excluded party is a direct biller, but the OIG has unequivocally stated that even volunteers can create both overpayment and CMP liability unless the goods or services they deliver or provide are “completely unrelated to Federal Health Care Programs.”[11]

The OIG’s authority to impose CMPs, as found in 42 CFR § 1003.150, is seen in the chart below. The OIG also has the authority to impose additional assessments for exclusion violations under that regulation, but with the enforcement tools already available to the OIG, there are no known instances where it has resorted to that option.

| Basis for Civil Money Penalty | Authority for Penalty Amount | Potential Civil Money Penalty |

|---|---|---|

| Presentation of the claim for an item or service by an excluded party. §1003.200(a (3) |

§1003.210(a)(1) | Up to $22,427 for each violation |

| Excluded party retaining ownership or control. §1003.200(b)(3) | §1003.210(a)(3) | Up to $22,427 per day for each day that the prohibited relationship occurs |

| Arranges or contracts with an excluded party. §1003.200(b)(4) | §1003.210(a)(4) | Up to $22,427 for each item or service provided or furnished ((separately or non-separately billable) |

| Orders or prescribes medicine from the excluded person. §1003.200(b)(6) | §1003.210(a)(1) | Up to $22,427 for each individual violation |

| MCO employs or contracts with an excluded party. §1003.400(b)(2) | §1003.410(a)(1) | Up to $42,788 for each individual violation |

| MA and Part D contracting org. employs or contract with excluded party §1003.400(c)(5) | §1003.410(a)(1) | $42,788 for each individual violation |

It is important to note that even when a provider is unaware that a person was excluded upon hire or at the time the claim was made, OIG has issued guidance advising that such inadvertent violations must be reported and repaid.[12] light of this guidance, any claim that might involve an excluded person or entity could potentially have implications under the Affordable Care Act if it is not dealt with in a timely and proper manner.

VI. Avoiding the Risk of CMPs and Overpayments

Exclusion enforcement is based on the simple premise that providers have a duty to confirm the exclusion status of their employees and business associates and exclusion violations occur when providers fail to uphold this responsibility. Hence, the sole method to avert or lessen these risks is by undertaking all sensible measures to conduct thorough exclusion screening.

In light of the broad scope of the payment prohibition, this can best be accomplished by screening all employees, vendors and contractors upon hire or the initiation of the relationship, and monthly thereafter with the the OIG’s List of Excluded Individuals and Entities (LEIE). This is also consistent with the OIG’s Updated Special Advisory Bulletin on the Effect of Exclusion Participation in Federal Health Care Programs issued May 8, 2013. it is also advisable that providers exercise caution if they choose to selectively screen direct employees and providers.

The OIG recommends that providers use the same screening criteria for vendors and contractors as they do for their employees. While this does not always translate well, since the goal of CMPs are to safeguard the programs and beneficiaries, “[t]he risk of potential CMP liability is greatest for those persons that provide items or services integral to the provision of patient care because it is more likely that such items or services are payable by the Federal health care programs.”[13]

Corporate Integrity Agreements resulting from False Claims Act Settlements provide some additional insight in the OIG’s view of screening requirements. On one hand, a common limitation found in them is providers are not required to screen vendors whose “only link” to the provider is selling or supplying equipment or materials, for which the vendor does not bill. This sensible exception clears up confusion regarding a large group of vendors who supply items for which the provider is ultimately reimbursed. On the other hand, however, these agreements often require that owners, officers, directors, managing employees, agents, and active medical staff must be screened, irrespective of their direct or indirect employment status be screened.

VII. Conclusion:

The focus of this article is to help providers understand their obligations with respect to exclusions, the risks they face if they fail to meet them, and how best to avoid those risks. Our other posts have additional information, but if you have any questions about exclusions and your screening obligations, feel free to contact any of us at Exclusion Screening, at 1-800-294-0952 or fill out the form below.

Click here to read more about How the LEIE, GSA/SAM, and State Exclusion Lists Differ; And Why They Need to be Screened

Paul Weidenfeld is a former federal healthcare fraud prosecutor and Department of Justice National Health Care Fraud Coordinator. His principal area of practice is healthcare fraud and abuse and the Federal False Claims Act, and he has represented providers and individuals in healthcare matters since leaving government in 2006. Mr. Weidenfeld also has an extensive litigation background that includes numerous trials and appeals and appearances before the United States Supreme Court, the Federal 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Contact Paul should you have any questions at: pweidenfeld@exclusionscreening.com or 1-800-294-0952.

[1] Since States have separate authority to restrict participation in their programs, the term “OIG Exclusion” is used to distinguish federal administrative exclusion actions from those which States may take to limit provider participation in their respective programs For example, many State actions are called “Terminations” (the term which is used by Federal Regulations).

[2] Authority was first granted to the Department of Health Education and Welfare in 1979. The agency was later renamed the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and it was delegated to the Office of Inspector General in 1988 (53 Fed. Reg. 12,993 (April 20, 1988)). See also, 42 CFR 1003.150.

[3] The Medicare-Medicaid Anti-Fraud and Abuse Amendments of 1977, Public Law 95-142. In 1981, the Civil Money Penalties Law (Public Law 97-35) extended the authority to impose penalties from those convicted of program fraud to providers that submitted claims for items or services that had been furnished by an excluded entity.

[4] Mandatory exclusions are found in 42 USC § 1320a-7, Sections 1128(a)(1) through 1128(a)(4) and 1056 of the Social Security Act;

[5] Permissive exclusions are found in 42 USC 1320a-7(b), Sections § (b)(1)-(b)(17) of the act.

[6] 42 C.F.R. 1001.1901(b), 42 C.F.R. § 1001.10).

[7] (Refer to 2013 Special Advisory, pages 6 and 7).

[8] 2013 OIG Special Advisory, at 11-12, 16;

[9] 42 C.F.R. §§ 1001.2001- 1001.2007.

[10] The authority to impose penalties for exclusion violations is found in 42 CFR § 1003.150

[11] 2013 OIG Special Advisory, at 11-12, 16;

[12] Ibid.

[13] the likelihood of patient harm resulting from the conduct is highly relevant to both the imposition of screening and penalty propositions for violations. 2013 Special Advisory at 16; See also 81 Fed. Reg. 88, 334, Dec. 7, 2016.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the effect of an OIG Exclusion?

Federal health care programs (Medicare, Medicaid, CHIPs, TRICARE, etc.) are prohibited from paying for any item or service furnished directly or indirectly by excluded parties. It is a complete ban on payment that extends to all services, not just those billed directly, and to all methods of payments. In addition, providers of services to these programs may not hire or contract with excluded parties. The consequences of the payment prohibition can be severe. All reimbursements made in violation of it are overpayments which must be repaid, and civil money penalties can be imposed for employing or contracting with excluded parties. It is also noted that under the ACA, unpaid overpayments can result in false claims act liability.

Why are OIG Exclusions Imposed?

Exclusions can be imposed for a variety of reasons but the vast majority (about 90%) are imposed for convictions related to health care fraud, patient abuse, and offenses related to controlled substances, or for the suspension, revocation, or surrender of a license to provide health care based on professional competence, performance, or financial integrity. That said, the two largest categories outside those identified above are defaulting on federal education loans and for the transfer of an excluded entity to a family member or member of the household to avoid the consequences of an exclusion (which together amount to about 5%).

what is the oig exclusion list?

The OIG, The Office of Inspector General’s “List of Excluded Individuals and Entities” (LEIE)

The Office of Inspector General for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS/OIG, or OIG) has the authority to exclude individuals and entities from participating in federal health care programs. The List of Excluded Individuals/Entities (LEIE) identifies all persons and legal entities currently under an exclusion sanction, and providers must ensure that they don’t employ or contract with anyone on the list.

The LEIE currently has 78,927 entries. It is maintained and updated monthly by the OIG, and it can be accessed on the OIG’s website. The LEIE can be searched directly on the website or downloaded in its entirety from the site in excel format and it contains sufficient information for providers to determine if someone they want to employ or contract with is excluded.