Category: All

Civil Monetary Penalties

Browse through our comprehensive resources designed by exclusion experts to offer you support and guidance.

April 22, 2025

We are sometimes asked, “Why do you screen against the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System...

April 15, 2025

The OIG’s November 2023 Compliance Guidance The OIG’s November 2023 Compliance Guidance lists 7 elements...

June 19, 2024

This article focuses on helping providers understand New York Medicaid exclusion screening law, and its...

April 26, 2024

Alabama’s Medicaid Program will not pay for any item or service furnished by, or at the medical direction...

April 22, 2024

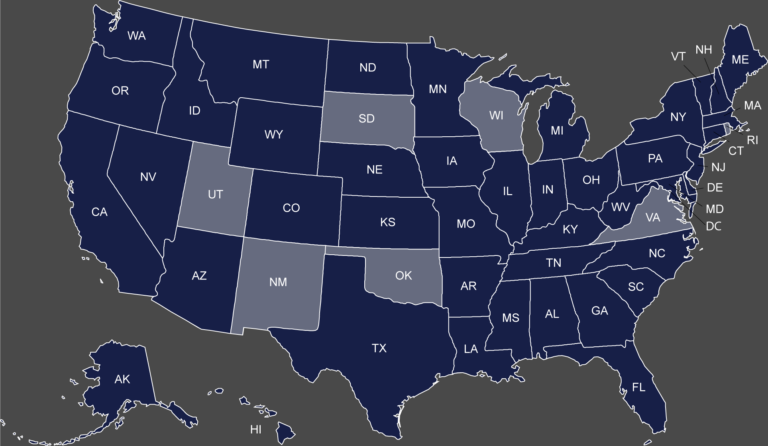

Map of the States with a Separate Medicaid Exclusion List Click on your state to view their Medicaid...

April 22, 2024

OIG Exclusion List vs. CMS Preclusion List Since the CMS Preclusion list was announced in April 2018,...

April 16, 2024

We have previously discussed that once a provider is excluded he may not furnish items or services...

March 21, 2024

What are the California Exclusion List Screening requirements? The Medi-Cal Program will not pay...

February 28, 2024

The Pennsylvania Precluded Provider List, commonly referred to as “Pennsylvania Medicheck ,” identifies...

February 19, 2024

Exclusions and debarments are powerful administrative sanctions imposed by Federal and State agencies....

January 16, 2024

The importance of screening employees, vendors and contractors against available federal and State exclusion...

November 17, 2023

Most healthcare providers and suppliers in the State of California are aware that exclusions imposed...

November 14, 2023

A Provider’s Guide to OIG Exclusions: Federal Exclusion Regulations and Enforcement Authorities, and...

November 10, 2023

OIG Exclusions are powerful enforcement sanctions that bar an individual or entity from any participation...

October 1, 2023

At Exclusion Screening, we often receive questions about the scope and frequency of an organization’s...

August 31, 2023

I. Introduction The Office of Inspector General (OIG) has the authority to exclude providers from participating...

March 2, 2022

The last two years have been rough for everyone, and it has been particularly difficult for healthcare...

November 2, 2021

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)[1] is the Federal agency tasked with the overall...

October 25, 2021

Medicare and Medicaid providers / suppliers are prohibited from employing individuals who have been excluded...

August 23, 2021

To understand the North Carolina Exclusion Screening Requirements, we must first touch upon Exclusions...

April 28, 2021

I. What is the NPDB The National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB) was created as part of the Health Care...

January 8, 2021

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Inspector General (OIG) is responsible for...

December 22, 2020

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Inspector General (OIG) exercises both mandatory...

November 23, 2020

Exclusion Actions Under 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7(b)(5)(B) (November 2020): Since 1976, the Department...

April 1, 2020

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Inspector General (OIG) may be required...

March 30, 2020

After finding a confirmed exclusion among your employees, vendors, contractors, or volunteers there are...

January 16, 2020

Massachusetts Medicaid Exclusion Screening: Requirements and Best Practices for Compliance The Massachusetts...

October 9, 2019

Should you choose to participate in the Medicare and/or Medicaid programs, you must comply with a wide...

September 26, 2019

Over the past year, both State and Federal law enforcement investigators and prosecutors have gone to...

June 10, 2019

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) recently published its Semi-Annual Report to Congress covering...

May 3, 2019

(May 2, 2019) The Alabama Medicaid Program imposes significant exclusion screening requirements on its...

April 8, 2019

(April 4, 2019): In December of 2018 a study was conducted by Kyle Wench (George Washington University)...

April 2, 2019

(April 2, 2019) The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Inspector General (OIG),...

March 1, 2019

(March 1, 2019) The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Inspector General (OIG),...

February 13, 2019

Beginning April 1, 2019, the new CMS Preclusion List will go into effect subsequently barring many healthcare...

February 7, 2019

By Cason Liles (February 6, 2019): The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of...

February 6, 2019

(February 6, 2019) The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Inspector General (OIG),...

December 17, 2018

(December 17, 2018): Texas Medicaid Exclusions will prevent the Texas Medicaid Program from...

August 30, 2018

(August 23, 2018): In 2008, after learning that a Texas-based laboratory services company was submitting...

July 30, 2018

Perhaps the most severe administrative sanction available under the Social Security Act stems from the...

January 22, 2018

(January 22, 2018): With 2017 behind us, it can be quite helpful to review the Medicare “exclusion”...

January 12, 2018

(January 12, 2018): The Medicare and Medicaid programs are both essential, yet costly health benefit...

January 8, 2018

(January 8, 2018): Most physicians will progress through their entire career without ever having...

December 22, 2017

Year in Review OIG Podcast Earlier this week, the Office of Inspector General released its “Year in Review”...

August 16, 2017

(August 16, 2017): Earlier this summer, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) executed its most extensive...

June 8, 2017

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has recently entered into a number of exclusion case settlements tied...

May 26, 2017

Exclusion News (May 22, 2017): By Paul Weidenfeld Health Care Fraud will continue to be a high priority...

May 3, 2017

The recently issued Resource Guide for Measuring Compliance Program Effectiveness, reconfigures the traditional...

March 29, 2017

By Paul Weidenfeld The new Final Rule issued by CMS revising the conditions of participation for home...

February 13, 2017

In what appears to be a growing enforcement trend, the Department of Health and Human Services, Office...

January 31, 2017

Exclusion Violation by Dentist “Sends a Strong Warning” February 1, 2017 By Paul Weidenfeld...

January 24, 2017

By Paul Weidenfeld January 23, 2017 On January 12, 2017, the Office of Inspector General published a...

December 16, 2016

DOJ Announces $4.7 billion in FCA Recoveries By Paul Weidenfeld December 16, 2016 The “Third Best...

September 7, 2016

OIG Imposes Record $21.5 Million in Penalties for Exclusion Violations! The OIG imposed a record $21.5...

August 9, 2016

[1] The Office of Inspector General (OIG) has steadily increased its enforcement of OIG Exclusion Screening...

August 2, 2016

By Robert W. Liles. August 3, 2016. The False Claims Act is the primary...

May 4, 2016

On April 18, 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (HHS-OIG)...

March 4, 2016

I. The OIG Reinstatement Process Most exclusions are imposed for a definite time period. The question...

March 4, 2016

By Paul Weidenfeld, March 4, 2016. An essential element of all compliance plans is developing and...

December 4, 2015

The Office of Inspector General’s 2016 OIG Work Plan contains two important projects that focus...

October 12, 2015

In August, we discussed an OIG audit, which revealed that Medicaid providers who were terminated for...

September 23, 2015

The failure to report excludable offenses by state Medicaid offices and licensing boards is a longstanding...

September 8, 2015

In February, we reported that the Michigan Attorney General secured a racketeering and health care fraud...

September 1, 2015

In late July, a federal district court in Pennsylvania joined in the flurry of False Claims Act (FCA)...

August 27, 2015

OIG has been busy cracking down on providers who employ or contract with excluded persons or contractors. ...

August 26, 2015

The owner of a New Jersey ambulance company was indicted for health care fraud in mid-August of...

August 21, 2015

Our experts at Exclusion Screening, LLC maintain fact sheets that contain the screening requirements...

August 20, 2015

https://www.exclusionscreening.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Why-do-you-need-a-compliance-Hotline.mp4...

August 14, 2015

In early August of 2015, the Southern District of New York (SDNY) provided insight as to when the...

August 11, 2015

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) creates a 60‑day window to report and return overpayments from Medicare...

August 10, 2015

OIG Audit Findings In a recently released audit, the OIG found that despite the ACA requirement...

July 29, 2015

DOJ Pursuing Action on Two Separate OIG Exclusion Violations The U.S. Attorney’s Office in Philadelphia...

July 23, 2015

Assistant Inspector General Testifies before Congress Ann Maxwell, the Assistant Inspector General for...

July 1, 2015

Exclusion Screening, LLC has been chronicling the Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) interest...

June 30, 2015

This article was written by Paul Weidenfeld [1] By now, providers should be aware that the Office of...

June 22, 2015

Exclusion Screening Is Mandatory Providers of medical services that participate in Federal or State Health...

June 16, 2015

The Department of Justice (DOJ) recently announced two new False Claims Act (FCA) settlements involving...

June 16, 2015

(This article was originally posted in the National Alliance of Medical Auditing Specialists‘ “Tip...

May 17, 2015

Home Health Agency Excluded for Employing Excluded Nurse HHS/OIG recently issued a press release announcing...

April 29, 2015

I. Gains in State Exclusion Enforcement Efforts Highlighted The Office of the Inspector General’s...

April 26, 2015

Since August 2014, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) has collected roughly $3.75 Million in...

April 20, 2015

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) Broadly Interprets Exclusion Regulations OIG’s Demonstrated...

April 17, 2015

I. Hospital Employed Therapist with Lapsed License The Department of Justice (DOJ) entered...

April 14, 2015

I. Fraud Found in HHS’ Backyard A Virginia contractor for dental providers was recently indicted...

March 18, 2015

I. OIG Targets Nursing Homes Last year almost half of the exclusion violation matters reported by the...

February 19, 2015

I. Excluded Podiatrist Commits Health Care Fraud A Michigan podiatrist who was excluded...

February 13, 2015

I. Advisory Opinion on Payments for Services Provided Prior to Exclusion The Department of Health...

January 29, 2015

I. CMPs doubled in OIG Exclusion Violations 2014 Exclusion Screening, LLCSM dedicates a significant...

January 28, 2015

I. OIG Report In the Office of the Inspector General’s (OIG) semiannual report to Congress,...

January 21, 2015

Providers are often surprised to learn that a person can be excluded from participation in federal health...

January 19, 2015

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) issued a Special Advisory Bulletin in May 2013, which states...

January 2, 2015

I. Federal and State Agencies Conducting Audits As many healthcare providers and suppliers have painfully...

December 17, 2014

I. Civil Monetary Penalties Twenty-five out of the fifty-five exclusion enforcement actions reported...

December 2, 2014

At Exclusion Screening, LLCSM, we know the ins-and-outs of the exclusion screening process. In our opinion,...

November 24, 2014

I. Mandatory OIG Exclusions When the Office of Inspector General (OIG) considers imposing a mandatory...

November 20, 2014

I. OIG Recommends Monthly Screening While there is not a formal regulation that mandates monthly...

November 20, 2014

[visualizer id=”1978″] A quick review of the Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) exclusion...

November 17, 2014

I. Florida’s State Exclusion. Excluded Providers Costs OIG Over 2.7 Million The Office of...

November 12, 2014

HHS/OIG Deputy Inspector General Gary Cantrell testified earlier this year that States are failing to...

November 12, 2014

I. Take It from CMS: If You’re Excluded in One State, You’re Excluded in All States...